Paint is the outer skin on most of our creations. It is

almost essential on metal because so many of them, especially the useful ones,

are vulnerable to the atmosphere. Worse

still, with a Wrightscale product which uses several different materials, some

components need more protection than others.16mm Wrightscale Wren seen below is protected by a skin of paint.

When these parts are bound together by an outer skin, then they perform better overall.

Paint, like skin on animals and humans, helps identify the individual and is pleasing to the eye. You don’t have to be an evolutionary biologist to realise that what is functional also has an aesthetic. ‘Fit’ may take many words to define but is recognisable in an instant.

Take for example the Wren, Malcolm’s first locomotive.

The chassis is built from a nickel silver etch. Nickel silvers are copper alloys with additions of zinc and nickel. They are described as ‘silver’ because of the silvery finish and resistance to tarnish. The particular alloy used in the etch was chosen for its mechanical properties and ease of fabrication. The etch is folded up, like origami, and held together with tabs. (And solder) Though tiny, the Wren has to be tough.

Into the folded nickel silver are introduced bronze bushes for the axles. No axles, no wheels, no wheels, no movement! Bronze was chosen for slightly different qualities when compared with nickel silver. It is highly ductile – that is – it has great potential when being shaped. It also, ah, how shall we put this? exhibits low friction when moving against other metals. When an axle moves in a bronze bush, it doesn’t scrape and grind and otherwise misbehave. On the other hand, a bronze bush very gradually wears away and must very occasionally be replaced. It oxidises slightly on exposure to air. It appreciates paint or varnish. The axles of the Wren have to be made of another alloy, extra hard yet flexible.

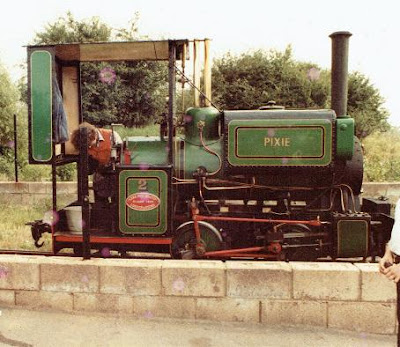

To give a model a 'prototypical' look, as with Pixie snapped at the Leighton Buzzard Line, weathering on top of a good paint job is recommended. Photo by MD WrightSome components have to be soldered, some ‘push-fitted’. Paint protects the parts which tarnish or rust, enables water or oil to run off the surface and makes the model look good. As importantly, the paint provides the model with its livery.

Livery is the badge of belonging. The Wrens used by Devon County Council or for sand extraction at Leighton Buzzard moved under their own distinctive colours. The surviving Wrens have the colours of their proud owners. Pixie, when she moved from Devon, worked the Leighton Buzzard in green livery. Her sister, Lorna Doone, is recognisable in a fetching blackberry shade. Peter Pan spent some years in blue. The livery is something each would-be owner has thought over carefully before making a purchase. Malcolm recommends certain shades, as you can see below.

The liveries of the prototypes tended to stick to certain shades dictated by the technology of paint. Paint itself consists of a pigment or it fails to perform its primary function, imparting colour (black and white included here). It also needs a binder or it doesn’t stick and a solvent. This enables it to flow on to the surface and then evaporates away, leaving pigment and binder behind. Lastly, most paints contain additives, anything from an anti-rust preparation to mould suppressant or insecticide depending on what is being painted. Modern paints contain a wondrous range of substances, reflecting the research and development of human kind.

Wrightscale 16mm Wrens viewed in green livery . Photo Malcolm WrightBefore the 20th century, the pigments available for painting locomotives were limited. Pure carbon provided black, a popular colour. Lead oxides provided reds and white, plus a degree of protection against corrosion. These were stable pigments. Green was provided by variations on copper and arsenic. Chromium green oxide, somewhat safer, was introduced later in the 19th century. It was fair to say that most of these pigments were poisonous to some extent – but they were durable!

Blues based on cobalt were expensive. Yellow was provided by cadmium, strontium, barium and zinc but yellow was really best for highlights and lining. Minor railways of the standard gauge felt obliged to take these less popular colours. It explains why red, black and green were the most popular liveries for the small narrow gauge prototypes for 16mm scale modelling.

There was one exception, photographic grey. As photography developed, forward-looking producers wanted the ‘factory shot,’ a photograph of completed rolling stock. The trouble was that only black-and-white was available in those days. It was almost impossible to get a good ‘shot’ of a black locomotive. Red and green were also a problem. Bayer Peacock was among the first to use ‘works grey’ for publicity shots, every detail visible. Armley Museum, Leeds, provided us with a beautiful works photo of the Wren which looks good in black and white.

We haven't really got far into the 20th century yet, or how paint has escaped from lead, arsenic and other 'nasties'. More from the Wrightscale workshop soon ...

No comments:

Post a Comment