Saturday 3 July 2021

16mm Couplings

Saturday 19 June 2021

Soldering Live Steam

Monday 24 May 2021

Glue or solder?

Saturday 1 May 2021

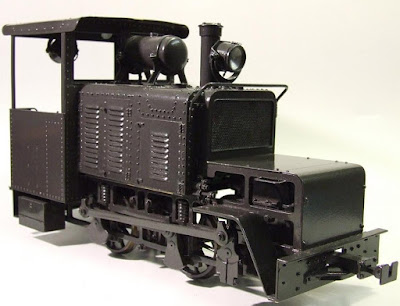

Proud owners of a 16mm Baldwin Gas Mechanical

Saturday 3 April 2021

Colonel Péchot and modern issues

Saturday 27 March 2021

Wrightscale and ethically sourced products

Much has been said about buying from reputable suppliers – who respect their contractors and the environment. Items which are sourced responsibly are likely to offer a longer lifetime of service and to have better guarantees of workmanship. We can also use the ‘power of the purse’ to influence bad regimes and irresponsible suppliers.

|

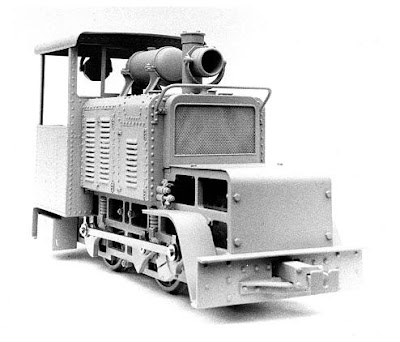

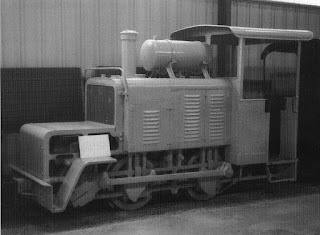

| Wrightscale WD Baldwin 4-6-0 in 16mm scale |

Disappointingly, suppliers know the power of the purse. Rather than fix problems, they try to mislead their customers. The worse they treat their workers, the more likely they are to lie to the public. The Public Relations Department of Apple, for instance, have been caught out in blatant untruths about workers’ welfare (more in my next blog).

Don’t trust everyone!

Unfortunately, very little manufacturing remains in this country and so we are forced to source many of our purchases from abroad. In itself, this makes repair and recycling difficult and the transport involved requires much in the way of resources. It also makes it harder to check on the welfare of workers.

Where we can use the ‘power of the purse’ more effectively is in discretionary spending. We model railway enthusiasts know that many tempting products come from foreign sources. This usually means China where most of our model railway ‘names’ have arrangements with Chinese factories.

|

| Another Wrightscale classic. Accept no imitations |

Now it is true that most Chinese employees are quite well paid and can take foreign holidays or study abroad. They could choose to live away from Shanghai or Gwangzhou, but many of them actively like the ’buzz’ of a busy city. What we might find crowded, they consider normal and natural. They find rural Scotland or La France Profonde rather unnerving, preferring instead to spend their holidays in the crowds of Princes Street or Tottenham Court Road.

Unfortunately, we have to accept that this growing prosperity depends on a hidden army of cheap labourers. In China, as in other jurisdictions, this can mean prisoners. There have always been prisoners expiating ‘crimes against the state’ but recently, numbers have grown. A million Uighurs, and others, have gone for re-education. After this process, they are not released. According to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, a sizeable fraction of this million are used in government labour transfer schemes. People are basically rented out to factories. These claims have been checked and, sadly, further organisations and their factories have been shown to use these tied hands..

Large western companies have been named and shamed – Sony, Volkswagen, Nike and Apple. Their PR departments aver that ‘thorough audits of workers’ welfare’ take place. TTP, a US human rights group has found a number of embarrassing documents, even film clips online. These suggest an uncomfortable truth about some of the workers producing items for these big ‘names’. Many are badly treated and company audits are not thorough.

|

| Wrightscale products are made in a clean and airy environment |

Complete 100% auditing is difficult, even for a large company. There is more in a further blog.

Many smaller companies, including manufacturers of 16mm scale models have also outsourced their manufactures to China. Given that some of these companies are run by a small number of executives, not chosen for their language skill, can we trust them to take care of workers in a foreign country?

As suggested before, the upper, above-surface layers of these manufacturies consist of well-qualified employees. These would be the managers, purchasers and sales-force. The stratum below would also be skilled and well paid. These are the designers and tool-makers. Because this skilled elite is not numerous, there is competition for their services; their pay and conditions rise steadily.

I have a great respect for this elite. Much of their production is quite excellent. Unfortunately, they can apply their talents of reverse engineering in unfortunate ways. More in another blog.

It will be the assembly-line workers, cleaners and packers who are more likely to be badly treated. If I were a factory manager, these are the jobs I’d give to the ‘labour transfer’ scheme. The welfare of these workers would be the responsibility of the Chinese state, not me.

In an environment of fear and oppression, it is hard to enforce quality control. From personal experience, many items of Chinese manufacture look alright but fail after a few hours of use. If a customer complained, a new one would be supplied – up until about five years ago, without question.

As the cost of imports gradually increases, retailers are becoming less obliging. If the item was out of warranty, then too bad. In real terms, it didn’t cost much. As these items have been bought so cheaply, we probably don’t complain often enough. We have lost the habit.

Many railway model producers ‘off-shored’ their manufacture to China. To their credit, one or two such as DAPOL plan to bring production back to Europe.

Most Wrightscale production takes place in our workshop where recycling and workers’ welfare can be personally supervised. (More in a further blog)

We try without being trying!

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute ASPI is based in AUSTRALIA

The Tech Transparency Project (TTP) is based in the USA

Friday 19 February 2021

Paint and the Wrightscale BGM

Hello everyone. We hope that you are all staying happy and healthy after eleven months of lockdown.

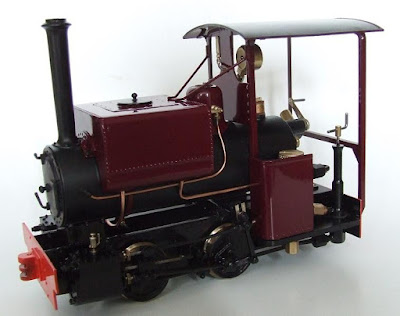

Wrightscale Baldwin Gas Mechanical in weathered French Horizon Blue

In the last blog, topic paint, we were wondering if beauty was really just skin deep. As far as our models are concerned, if paint is beautiful, it is only good to behold if it is also functional. Let’s look over Malcolm’s shoulder as he prepares to paint a Wrightscale model.

The beauty depends on good preparation. Firstly there is research. The model has to be faithful to the original, with a livery that reflects the materials which the original engineers had to hand. Preparation continues with the choice of suitable modern materials. When painting the 19th and early 20th century prototypes, the pigment, binder and solvent of the paint available came from a limited range. The range of ingredients is wider now, but planning is still required, followed by skill, training and an artistic sense.

Finally, the physical preparations can begin.

Then, as now, the locomotive had to be clean. The prototype locomotive was as clean a practicable, given the vast area, time constraints and a dusty atmosphere. In spite of their best efforts, tiny specks were caught by the paint. David Sharp uses ultra-modern IT to scan the surfaces of surviving prototype locomotives; the scanners are so good that they pick up all the ancient grime painted into the surface. David has to go through the files and give the virtual locomotive a virtual ‘clean-up.’

Pictured above is a partly restored Baldwin Gas Mechanical at the Apedale Preserved Railway, photographed by Jim HawkesworthA Wrightscale model is physically cleaned to remove visible material. The next stage is putting it through an ultra-sound cleaner which removes the most persistent or tiniest blemishes. After thorough drying, it is carefully dusted.

Paint brands which Malcolm has used successfully are Halfords Car Spray, Tamiya Modelling paints and also Warhammer model paints.

Then, as now, the first coat of is a primer which sticks fast to the surface of the locomotive or rolling stock. Then, as now, the primer has to ‘key.’ These days you might say it has to ‘bite’, a term which is more than metaphorical. Primers were often corrosive when applied. Why dry, they had bonded to the metal.

The primers Malcolm uses still come with warnings. Etch primer – the term comes from the German ‘to eat’ - has to be treated with particular respect. For some applications, however, it has to be used.

For many purposes, Halfords primer is good, but the container must, all the same, be treated with care. It would be helpful if they listed all the ingredients, but we can take an educated guess, having read the warnings on the side of the can. The can is potentially explosive and from that we can deduce that the solvent is a volatile organic compound.

A Wrightscale 16mm Baldwin Gas Mechanical in grey primerAnother of the warnings concerns temperature. The action of painting slightly heats the surface of the metal. This suggests that the pigment/filler consist of the components and catalyst which form acrylic plastic. This is held in solution until sprayed and then there is a chemical reaction. At the end of the curing process, the paint layer is bound into the surface. Any harmful chemicals have been dispersed.

Paint spray has a short shelf life. This also suggests that the contents can form acrylic.. Leave a spray can too long and the components cure inside the tin.

The paint can only form a bond with the locomotive surface if conditions are right. The surfaces must be clean, dry and dust-free, as we have seen. Temperature and humidity must be correct, and spraying must not happen in direct sunlight. We can see why Malcolm’s long apprenticeship as a chemistry teacher proved useful.

When satisfactorily primed, Malcolm can move on to the next coat, and the next, and the next, up to half a dozen times. Working at 1:19 scale, Malcolm can’t use prototypical painting techniques – no ladling it on with a brush. The odd fly or dust grain didn’t matter at 1:1 scale, but with a model, every coat must be thin, even and consistent, using paint sprays. Between coats, the equipment must be thoroughly cleaned. Any lumps of old paint which make their way on to the next job will be horribly visible.

The 16mm Baldwin Gas Mechanical viewed from the back. This shade of grey shows every detail and every mistake in merciless clarity. It is just as well that Malcolm doesn't make many mistakes!Here is his advice to a friend about painting:

Within reason, it does not matter how long a model is left between coats assuming all is kept clean and dry. Do a test spray before starting, perhaps on an empty spray can, to check that the paint has not begun to cure. This also gives you a feel for how the paint sprays and what it looks like wet, part dry and fully dry. Each coat should be even and very light

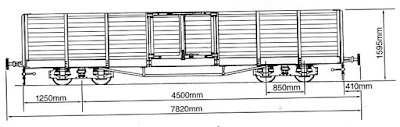

If it’s a small item such as a wagon, I usually complete one side before starting the other. Spray the end and one side and the inside which can be reached. Then the model can be rotated, repeat for other side and end, then leave to start to dry (15min). Then, upside down, repeat the above. As you are doing this, make 2-3 light passes of spray over the sole bars, steps and under-frame. Rotate the wheels each pass to prime the face and rear of the wheels on the opposite side. Then spray the underside of the other side and end as before. Try to end up with two good passes on the sides/ends and a little heavier on the under-frame and wheels. The flanges clean easily at the end.

A Wrightscale model is finished with a protective layer of varnish. Vehicle paint on top of the recommended primer, followed by the recommended varnish seems like a good job well done. It will perform well under normal conditions, that is, as long as the painted surface stays within the recommended temperature range.

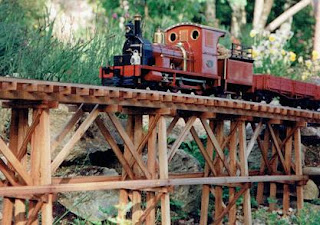

Wrightscale Baldwin Gas Mechanical, and friends, in khaki liveryThere is a ‘but’. For a 16mm scale locomotive, we have to admit that there is a slight gap between recommended and realistic temperature. Water levels vary between the beginning and the end of the run. That is what steam running is all about. If the boiler is nearly empty – which is in the nature of steam – the outside surfaces can get hot and the paintwork soft. It does make the locomotive hard to handle and marks the paint. This is a problem, we admit, and Malcolm is working on it.

There is also artistry, a topic we visit and revisit. A large surface, whether gloss or matt, gains a certain liveliness from reflections. Malcolm loves to convey this on a model. It’s the challenge, you see! He has a certain respect for Warhammer, the suppliers for a certain class of model warfare enthusiasts. They appreciate that what seems like the same shade of grey may have to include different qualities. Skull Grey or Wraith Grey may look the same to the uninitiated but in fact working out the base for these paints is a process of iteration and development. This sounds like marketing-speak, but Malcolm has found that the company knows its stuff. Using more than one shade from the range gives the surfaces of his locomotives new depths.

We come to the future. Even a studio as backward-looking as Wrightscale, creator of working models of 19th and 20th century prototypes, has to look forward. Malcolm uses non-ferrous metals, caustic substances and organic sprays with a heavy heart. At the moment they are necessary. Here comes the essential paradox of hazardous materials. The people who use them are the ones most eager to find replacements and the ones who probably will. We just cannot stress this enough.

Wrightscale Baldwin Gas Mechanical in fresh paintThe future offers tantalising possibilities, many from the natural world. The science of bio-mimetics, the looking for inspiration from the natural world, could be a great help. For example, a bio-glue copying some aspects of a slug’s secretions or a gecko’s toe, could play its part in paint primer. A bio-plastic made by an Australian bee could play its part in replacing acrylic in paint.

Or we could take a lesson from the tree. Like all living things, it needs trace elements. The soil provides these but as well as potassium, zinc and phosphorus which are essential to life, it has ‘nasties’ such as lead, cadmium and the so-called heavy metals, harmful to life. The roots of healthy trees have hidden helpers. Most root hairs are accompanied by fungal mycelia. These stretch further and seek more widely and have a fungussy intelligence. They take up the trace elements and tuck away the poisons. There is talk of using them to counter pollution.

The history of the Baldwin Gas Mechanical is described in Colonel Péchot: Tracks To The Trenches

‘The Hidden Life of Trees’ Peter Wohlleben describes some of the works of the fungus family

Monday 8 February 2021

Painting Wrightscale 16mm models

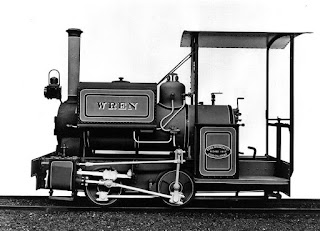

Paint is the outer skin on most of our creations. It is

almost essential on metal because so many of them, especially the useful ones,

are vulnerable to the atmosphere. Worse

still, with a Wrightscale product which uses several different materials, some

components need more protection than others.16mm Wrightscale Wren seen below is protected by a skin of paint.

When these parts are bound together by an outer skin, then they perform better overall.

Paint, like skin on animals and humans, helps identify the individual and is pleasing to the eye. You don’t have to be an evolutionary biologist to realise that what is functional also has an aesthetic. ‘Fit’ may take many words to define but is recognisable in an instant.

Take for example the Wren, Malcolm’s first locomotive.

The chassis is built from a nickel silver etch. Nickel silvers are copper alloys with additions of zinc and nickel. They are described as ‘silver’ because of the silvery finish and resistance to tarnish. The particular alloy used in the etch was chosen for its mechanical properties and ease of fabrication. The etch is folded up, like origami, and held together with tabs. (And solder) Though tiny, the Wren has to be tough.

Into the folded nickel silver are introduced bronze bushes for the axles. No axles, no wheels, no wheels, no movement! Bronze was chosen for slightly different qualities when compared with nickel silver. It is highly ductile – that is – it has great potential when being shaped. It also, ah, how shall we put this? exhibits low friction when moving against other metals. When an axle moves in a bronze bush, it doesn’t scrape and grind and otherwise misbehave. On the other hand, a bronze bush very gradually wears away and must very occasionally be replaced. It oxidises slightly on exposure to air. It appreciates paint or varnish. The axles of the Wren have to be made of another alloy, extra hard yet flexible.

To give a model a 'prototypical' look, as with Pixie snapped at the Leighton Buzzard Line, weathering on top of a good paint job is recommended. Photo by MD WrightSome components have to be soldered, some ‘push-fitted’. Paint protects the parts which tarnish or rust, enables water or oil to run off the surface and makes the model look good. As importantly, the paint provides the model with its livery.

Livery is the badge of belonging. The Wrens used by Devon County Council or for sand extraction at Leighton Buzzard moved under their own distinctive colours. The surviving Wrens have the colours of their proud owners. Pixie, when she moved from Devon, worked the Leighton Buzzard in green livery. Her sister, Lorna Doone, is recognisable in a fetching blackberry shade. Peter Pan spent some years in blue. The livery is something each would-be owner has thought over carefully before making a purchase. Malcolm recommends certain shades, as you can see below.

The liveries of the prototypes tended to stick to certain shades dictated by the technology of paint. Paint itself consists of a pigment or it fails to perform its primary function, imparting colour (black and white included here). It also needs a binder or it doesn’t stick and a solvent. This enables it to flow on to the surface and then evaporates away, leaving pigment and binder behind. Lastly, most paints contain additives, anything from an anti-rust preparation to mould suppressant or insecticide depending on what is being painted. Modern paints contain a wondrous range of substances, reflecting the research and development of human kind.

Wrightscale 16mm Wrens viewed in green livery . Photo Malcolm WrightBefore the 20th century, the pigments available for painting locomotives were limited. Pure carbon provided black, a popular colour. Lead oxides provided reds and white, plus a degree of protection against corrosion. These were stable pigments. Green was provided by variations on copper and arsenic. Chromium green oxide, somewhat safer, was introduced later in the 19th century. It was fair to say that most of these pigments were poisonous to some extent – but they were durable!

Blues based on cobalt were expensive. Yellow was provided by cadmium, strontium, barium and zinc but yellow was really best for highlights and lining. Minor railways of the standard gauge felt obliged to take these less popular colours. It explains why red, black and green were the most popular liveries for the small narrow gauge prototypes for 16mm scale modelling.

There was one exception, photographic grey. As photography developed, forward-looking producers wanted the ‘factory shot,’ a photograph of completed rolling stock. The trouble was that only black-and-white was available in those days. It was almost impossible to get a good ‘shot’ of a black locomotive. Red and green were also a problem. Bayer Peacock was among the first to use ‘works grey’ for publicity shots, every detail visible. Armley Museum, Leeds, provided us with a beautiful works photo of the Wren which looks good in black and white.

We haven't really got far into the 20th century yet, or how paint has escaped from lead, arsenic and other 'nasties'. More from the Wrightscale workshop soon ...

Tuesday 19 January 2021

Lessons From Silver Studio in Valuing Wrightscale 16mm

No apologies for looking at parallels with an eminent Silver Studio artist as we ramble on about valuing your Wrightscale models

|

| Wrightscale 15mm Excelsior models |

You like good pictures and it is interesting to consider the question: what constitutes a lifestyle asset.

Malcolm has inherited the copyright for Frank Price, the last Chief Designer of Silver Studio and so we can illustrate our thougts with piuctures from another art form. Our readers like original illustrations, so here we go!

Previously, I observed that a degree of scarcity increased

the value of a Wrightscale model. They are not produced in the volume that,

say, the fine plastic goods purveyed by LGB have achieved. Now, this blog post

goes on to argue the opposite. The fact that there are other models out there actually increases the value of yours.

An artist needs to put the work out there, for the benefit of previous customers as well as to increase future sales. Silver Studio is a case in point. As Philip Hook remarks, the most over-worked word in the vocabularies of dealers etc and here I would include fashionable merchants of fabric and wallpaper, is ‘iconic’. Thus for example, we have the Liberty print. The same dense, floral fabric patterns crop up from decade to decade and are still to be found in catalogues today.

|

| Design by Frank Price of Silver Studio. The original is 8 by 8 cm, that is at the stage where he would begin discussions with the client in this case possibly Liberty. Illustration courtesy MD Wright |

The underlying assumption is that the arts are good insofar as they are ‘typical’ or ‘recognisable’. A woman will pay a 10% premium for a blouse in a print which has her friends cooing ‘Ah! I so love Liberty!’ The pleasure goes both ways. The purchaser feels that the premium price was worth it. The friend feels pleasure in having spotted the iconic design. On the strength of their shared joy, they will indulge in another skinny cappuccino together.

Liberty owes many of its hallmark prints to the artists of the Silver Studio, especially to Frank Price.

Frank Price also produced chintzes, often inspired by older patterns. He gave them an edge, however, for example, updating an old Harry Napper birdie design.

Harry Napper was a highly respected Silver Studio designer 1896-1906. The brief for Price was to give it a modern edge. He did so by creating a design in three planes. One plane very cleverly seems to reach towards the viewer. The bird comes out to meet the observer. The supporting foliage is indicated on the second plane. Behind yet again are shadows.

As well as homage to Harry Napper, Frank has extracted the visual language of Japan, the use of shadows to underline reality. Silver Studio designs regularly borrowed from Japan and so, just as in the case of the Liberty fabric. The observer says ‘Aha!’

| Design by Frank Price for the Silver Studio SD16879. Reproduced courtesy of MODA, Middlesex University |

Unfortunately for Silver Studio and Frank Price, their names were not recongnised until too late, after the Studio closed.

There is iconic art and iconic Wrightscale. Malcolm’s Unique Selling Point is Live Steam in 1/19 scale, running on 32mm track. This already demanding characteristic is combined with accuracy, or, more correctly, fidelity to a prototype. These qualities were not chosen in an arbitrary way.

A model at this scale on that track is one that runs on real-life 2’ or 60cm gauge. This gauge was originally rather obscure, used by the very trail-blazing Festiniog (Ffestiniog) railway. The history and personalities appealed to him. Then the gauge ‘jumped’ to France. Narrow gauge innovators such as Decauville specialised in 40 and 50cm until a Captain in the French Army, Prosper Péchot, proved the worth of 60cm. The Army reluctantly adopted his ideas; the German Army copied him enthusiastically and soon the gauge was widely used. Again, this is quite a powerful story, moving from military exercises to the trenches of the First World War. After the French and Germans adopted the gauge, forestry railways and public carriers in Britain began to adopt it as well. Behind the ‘icon’ there is a genuine artistic voice.

|

| Wrightscale 16mm'Excelsior' in 0-4-0 configuration as used on the Kerry Forest Tramway |

This USP is unattractive to other model-makers. If they want accuracy, they go electric. If they want ‘Live Steam’, they go freelance. Wrightscale models have been pirated and reverse engineered, but the connoisseur can easily tell the difference. There are parallels with work fromn SIlver Studio. At the bottom of the Frank Price design can be seen ten coloured rectangles. Each on is a colour which has to be separatelyprinted on to the surface of the fabric. This requires 1000% more labour, much more skill and great possibilities for wastage.

You will observe the essential paradox in Malcolm’s art. There is a similar paradox found in Silver Studio. Both had chosen a USP which is tricky and 'uncommercial'. This tends to make them scarce. At the same time, there are/were enough examples out there to create a market.Even more importantly, there are enough people with the good taste to appreciate rare quality when they see it. For good quality 16mm scale, the possible market is between five and ten thousand, judging from the membership of the 16mm Association and the attendance at the AGM. Of course only a fraction would be possible purchasers. Under a thousand Wrightscale locomotives have ever been produced.

|

| Wrightscale 16mm model of 'Excelsior' in 0-4-2 configuration,as used until it was scrapped |

More would-be buyers than sellers? You have a rising market. Prices will go up.

If you are interested

Philip Hook Breakfast At Sotheby’s is a shrewd and humorous look at making money on the art market. It is well written. You can see that he even insists on an apostrophe in his title. Not many authors go for this level of detail.

For the full story of Festiniog to First World War by way of the French Army, read Colonel Péchot: Tracks To The Trenches

For more about the Silver Studio, look at the online archive of the Museum of Domestic Art and Architecture at www.moda.mdx.ac.uk

For more about Frank Price, read Frank Price: Golden Hand Of The Silver Studio

Saturday 2 January 2021

How to value a Wrightscale 16mm model

Silver Studio and 16mm; art has a link with money, so please read on!

Before going any further, we wish you all a happy new year.

Silver Studio ran from 1880 to 1965 in London. At first it produced 'everything for a well-furnished home' but it was always best known for fabrics and wall-paper. Its products are recognised as artworks, protected by international copyright law. Wrightscale too is a studio, recognised as such by the Federal Law of the USA and its products are artworks.

A Wrightscale 16mm Baldwin Gas Mechanical locomotive, finished in Field GreySilver Studio was dissolved in 1967 but many of its designs can still be purchased. Much work is now in the archives of Liberty, Sanderson, Warner and many celebrated fashion houses whose products are famous and pricey. The remaining intellectual property and unsold artworks were donated to Hornsea College of Art, London by Rex Silver’s heir. Hornsea College merged with others to form Middlesex Polytechnic and this in turn became Middlesex University. The archive became part of the Museum of Domestic Art and Architecture and still feeds into modern domestic design. To consult it go to www.moda.mdx.ac.uk

Art clearly means money. Wrightscale products claim to be art for various reasons.

They represent a degree of uniqueness. An oil painting stands alone, as does a single sculpture. When several bronze castings are made of a statue,these don't cease to be art. Just look at the auction prices! The same applies to woodcuts, fabric designs or the text of novels. They are protected, as are Wrightscale models. They represent a degree of art. They represent a vision of the world that has been made tangible. A ‘mute inglorious Milton’ isn’t an artist. No matter how wonderful the vision, if it has not some shareable reality, it’s not art.

This design comes from the Silver Studio Archive at MoDA - our thanks for allowing this to be reproduced. It is a sketch by Frank Price, the last Chief Designer. Though just a sketch, it has excited interest eg from Pinterest. Reproduction rights are expensiveThe world is full of tangible objects that do not qualify as art – coal, a loaf of bread. Many beautiful things, such as a view or a fascinating fossil aren’t art.

Both Silver Studio and Wrightscale products don’t fit quite

squarely into the Fine Art category. From around 1900 to the time of its closure, Silver

Studio designs were aimed to be copied for use around the world. Wrightscale models are prized for being consistent and yet also supply is limited by how many Malcolm can make.

The models, the fabrics and wall-paper are all designed to ‘do something’.The creator knows where he/she is going. Extremophile critics would claim that their very usefulness disqualifies them. Because they have an end, they are not the exploration that an honest-to-goodness-useless oblong of canvas or ‘art bronze’ can represent. To them, the true artist is Paul Klee taking a line for a walk.

A 16mm model, just like fabric or wall-paper is designed to fulfil to fulfil a purpose. This Wrightscale Quarry Hunslet is not just a pretty face. It is moving slate wagons. Does that make it less an art object?There are indeed borderline objects which are both

volume-produced but have artistic qualities. Our much prized bidet whose design

was inspired by Japanese porcelain is pleasing, well made and now has some

scarcity value. As a product of industrial design, it is an artwork. As a

bidet, it isn’t.We might auction it, but only on GumTree. It wouldn't go to Christies and certainly not to an auction of collectibles. to an auction of collectibles.

Art can be immensely valuable. Recognised artworks can go for huge sums of money. At the same time, and here’s the paradox, art is inclusive. No-one needs to be left out.

This detail from a design by Frank Price is also reproduced by kind permission of MoDA. The artist was clearly intending to bring some of the joy of Van Gogh's Almond Blossom - a priceless artwork to a wider public.16mm in general and the designs of Silver Studio belong within the territory of art. They have a functional existence, they invite the participation of their public and enjoying them is one of the most inclusive of human activities. Wrightscale models are bought because they work. In the same way, fabric has always been useful for covering, shelter and as a way of showing off.

Both have a contradictory quality. They are prized because failure is a possibility. Sometimes one of our locomotives doesn’t move. Sometimes a fabric doesn’t ‘work’ in a room. Time and care are needed. There is trouble shooting, there is rethinking. A relationship is built up between the person and the model, or indeed the family and their furnishings. As previous blogs suggest, this is slow pleasure, unlike the instant gratification offered by, say, a sugar hit, a violent movie or junk food. Once the savour is acquired, the pleasure of a tastefully furnished room or an afternoon on a 16mm live steam layout must be one of the finest human experiences.

Both the 16mm experience and appreciation of tasteful decoration are surprisingly inclusive. To experience the 16mm experience, all you have to do is to belong. To belong, all you need is to want to belong. A nominal subscription is needed, less than the price of regularly buying a magazine. You are then welcome at Society meetings. The only cost is getting there. In the same way someone can be a fabric artist. The story of Frank Price, Chief Designer at Silver Studio, illustrates this precisely. He came from humble beginnings, spent much of his working life among art treasures and left us all some of the finest designs in wallpaper and fabrics.

Association of 16mm Narrow Gauge Modeller www.16mm.org.uk

S. Wright ‘Frank Price: Golden Hand Of The Silver Studio’ Birse Press available from Camden Miniature Steam