Soon after the First World War ended, thoughtful engineers took stock of the railways used on the battlefields of the Western Front. Though there seemed a gulf between the Central Powers and the Allies, their trench supply railways were directly comparable, designed to be quickly installed, to take massive traffic and all to 60cm gauge. Frank G. Jonah, lately

in France in the American Expeditionary

Force (AEF) wrote a paper for the American Society of

Civil Engineers, New York,

March 3rd 1920. ‘They (German Railways) were extremely well built

and had a greater mileage than the French or American armies.’

|

| Friend and foe but compatible. A German D-Lok with tender shares the track with British War Department bogie wagons on this fine 16mm scale model of a World War 1 railway. Photo Jim Hawkesworth |

The history of the design went back many years. From about 1870, France,

Germany, Great Britain and the USA had portable track available. When Paul Decauville introduced his porteur Decauville, in 1875, it became

popular. It could be used in fields, factories

and quarries, even archaeological excavations. His jonction hybride was devised to make track-laying, even in the

dark, safe and relatively simple. Whichever end of prefabricated track was

offered up to existing track, the jonction

hybride ensured a fit. Soon, Decauville systems were being sold around the

world.

|

| Sections of Decauville portable track ended with one end with fishplates |

Between the late 1870s and 1888, Prosper Péchot regularly

visited the Decauville factory. He devised the Péchot prefabricated track and new

bogies and wagons which could take hitherto unimaginable loads. This Péchot

system was formally adopted by the French Army in 1888

The German Army adopted 60 cm gauge very soon after the

French Army did. and started using bogie wagons, just as had the French. Unlike

the French Army, they spent the years between 1888 and 1914 improving their

Feldbahn system.

By 1918, 60cm railways were widely used on the Werstern

Front by all participants, including the British, Canadians, ANZAC troops and

the AEF. Prefabricated track was used, especially for rapid, initial lay. This

was replaced with rail laid on sleepers as many photographs attest.

The German prefabricated track was as well designed as

anyone’s. No doubt after careful examination of the Péchot prefabricated track,

they understood that the sleepers (railway ties) performed much better if they

enclosed the soil/ballast rather than letting it shoot out under the weight of

a train. The manufacturer Paul Decauville refused to cooperate with the Germans

and so they designed their own sleeper. It was rather simpler than the elegant

box-shape that required the latest in Decauville steam-presses, but it did the

job.

In the same way, they did not use the jonction hybride as devised by Decauville. The Germans came up with

a rough-and-ready solution which attracted the admiration of Mr Jonah.

|

| A short section of Feldbahn prefabricated track. The standard length was 10m. Picture taken at Apedale Railway, Staffs, by MD Wright |

‘One end of the 5m

section of built-up (prefabricated)

track had a pair of bars with a hooked projection while the other end had the

flange of the bars bent up. In laying track, the hooked bar engaged the bent-up

flange of the last section.’

|

| Link between sections of German prefabricated track. Illustration adapted from Frank Jonah's illustration. Courtesy Jim Hawkesworth |

I do not mean to say that German track was inferior to

French. It was different.

These railways, whether French, German, American or British War Department, could be laid with amazing rapidity on

unpromising ground, quickly repaired and quickly lifted. Frank Jonah commented:

‘The speed with which

tracks could be constructed by the different Allied armies was practically the

same… A mile of track, including ballasting, required 2,100 man-days of

labour.’ All the same, it was much easier to lay short lines over virgin ground

than to build long supply lines over ravaged terrain. As we shall see below,

some track required even more labour.

In his words, these 60 cm railways were

among the chief agencies of transport:

‘The transportation of supplies necessary for the dense

concentration of men at the Front could not be accomplished satisfactorily on

the highways … therefore orders were given for the development of a

comprehensive system of Light Railways for the following primary reasons –

- To relieve the highways of traffic. In addition to the wear and tear on motor vehicles and the excessive use of gasoline, the wear on the roads was leading to a heavy traffic in road material so that a large part of the traffic hauled …. was to repair the damage which their own traffic was creating. And there was a saving of labour.

- To assist in rapid advance over shell-torn area

- To convey road material.

- To reduce manual labour at the Front.

These lines were developed so completely that eventually

nearly all heavy material was transported by Light Railways leaving the

highways clear for light fast-moving automobiles, trucks and ambulances.’

In the view of Jonah, the finest section of track built by

the AEF was the connection between AEF central at Abainville and the American

Front at Sorcy. I mention it, because it took the idea of prefabrication to a

whole new level. This was not just lengths of track, it was whole bridges!

|

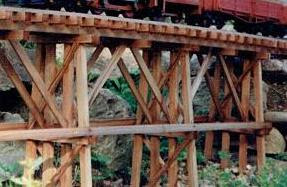

| A 60cm railway bridge was made from repeats of a section of prefabricated design |

Trestles were prefabricated from 5” by 10” road plank. These

were used for smaller bridges. For a long span, the approaches were supported

on trestles. The central section, two-deck Howe trusses fitted the

conditions. Units were normally of the

order of 4 ½ tons. They were lifted into position with a 5 ton locomotive crane.

Bridges were used, not only to cross streams and canals but

also standard gauge railways. A completed bridge was kept in reserve at

Abainville.Such was the enthusiasm of Frank Jonah, that he designed a

counter-weighted lift bridge (think Tower Bridge in London) all in timber.

You may be wondering why the AEF had their main depot so far

from the Front. Abainville was chosen because it had ‘ample space for a large

yard, with standard gauge rail and canal connections … It was directly behind

the St Mihiel and Argonne fronts on which the greater part of the American

operations were conducted. Abainville was 35 km (22 miles) back of the line. …

Material coming up from the ports was unloaded at the yards and taken to the front

as required’

Several interesting engineering problems were presented in

its construction. To be sheltered from German long-range guns, it was in rough

terrain. As it was near canal and railway connections, these had to be

carefully crossed. The light railway had to be reliable. An average speed of construction

was 2,460 man-days of labour.

The Germans also had timber bridges. They could be

single-deck as one pictured in in the Verdun

sector on the German side of the Western Front. My illustration is a detail

from a postcard entitled Argonnenwaldbahn (Argonne Forest Railway). These were

sold to help the War Effort. It comes from the collection of Raymond Duton.

|

| Detail of a German timber bridge in the Argonne 1917. Photo by Sanwald and Esslingen. Courtesy of Raymond Duton |

Timber bridges could be double height as in one near

Tilsit (now in the Russian territory

of Kaliningrad).

German bridges provided slightly different solutions to the

same engineering problem – how to use the triangle as much as possible, without

wasting too much timber. They too had repeating units but unlike the AEF, their

bridges did not consist of milled 5” by 10” plank. They used timber 'in the round', sometimes

not even straight timber.

The Allies gradually learned more about the German railway

systems so that, by 1920, Frank G. Jonah was quite an authority about them.

As the summer of 1918 progressed, the Allies captured an

increasing share of the territories once behind German lines. With the

territories came material, including rail, rolling stock and locomotives of

their 60cm Feldbahn system. Once the AEF finally swung into action they fairly

hammered the Germans.

|

| The AEF in training 1917-18. Photo from Illustration magazine. Courtesy MD Wright |

See more in Colonel Péchot: Tracks to the Trenches – Sarah

Wright

Narrow Gauge and Industrial Railway Modelling Review no 66

Heeresfeldbahn der Keiserzeit - Fach and Krall

Narrow Gauge To No Man's Land - Richard Dunn

No comments:

Post a Comment