As you know, many years of fascination with the life and

works of Prosper Péchot (1842-1928) resulted in my book, Colonel Péchot: Tracks

To The Trenches. His near contemporary, Paul Decauville (1846-1922) lived through

the same experience of war and peace in France. The two were closely linked and were both awarded the

Légion d’Honneur for contributions to narrow gauge railways. In later life,

they were frenemies. The railway ran through their most formative years, though

the two men reacted to their childhood in different ways.

|

| Prosper Péchot in 1907, after he had been awarded his Légion d'Honneur. Courtesy Raymond Péchot |

Here are what I feel are significant events in their lives. Decauville

was born into a prosperous farming family near Evry south of Paris. Péchot was born to a bourgeois family

in Rennes. His

father was a well-regarded surgeon and his mother came from a family of

merchants. In those days, Rennes was still out

on a limb, a long stage-coach drive from Paris,

but during Péchot’s early years his father got a job in the Metropolis. He thus

learned at first hand the benefits of connectivity. If you wonder why there

aren’t many railway related pictures here, the reason is simple. There were

very few railways in France

at the time – in industrial areas of the northeast, and the eastern Massif

Centrale.

|

| Paul Decauville in later life. Courtesy Roger Bailly |

In 1848, there was revolution throughout Europe, not least

in France.

The then monarch was Louis Philippe, a so-called regent on behalf of a small

Royal child. At the hint of trouble, he fled. France

declared a Second

Republic - the first republic

had of course been after the French Revolution. It came in with high ideals.

‘The government will be by the people for the people. With liberty, fraternity

and equality as its first principles, the people will be its standard and

guide’ (my translation). Sisterhood was not mentioned and universal suffrage

did not include women.

A new provisional government moved against the most irksome

laws: press censorship, laws against free assembly and restrictions on who

could join the National Guard were all removed. Almost immediately, they

arranged an election open to all Frenchmen aged over 21. From 200,000 voters,

the franchise leapt to over 9 million. Anyone over 25 with a deposit (indemnité

parlementaire) of 25 francs could stand for election. These were heady days

indeed! No-one in fact protested. Though both Péchot and Decauville were both

very young, their families well remembered the national excitement.

Unfortunately, by early 1849, disillusionment soon set in. A

newly formed socialist government was voted in but were not able to satisfy the

expectations which had been raised. There were many unemployed who noisily demanded employment.

The government started National Workshops. Two large

building projects were needed, the railway stations at Saint Lazaire and at Montparnasse. These were a splendid idea – both to relieve

poverty and improve the national infrastructure – the railways of France were lagging far behind those of Britain and Germany.

These national workshops would be run like the Army with

officers, platoons etc. Unfortunately, this army was overwhelmed by the army of unemployed – 10,000 at least. Rather than face a riot, the

officers employed the tactics of any

sensible administrator. They employed the most likely people at

the agreed wage of 2 francs daily and put the others on furlough at 1.5 francs.

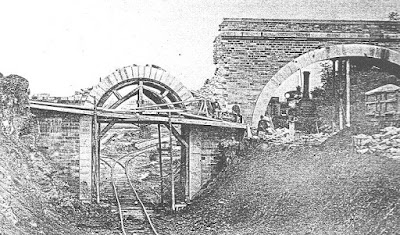

|

| Railway under construction. This one, running across Britanny, was not built for several more years. Courtesy Raymond Péchot |

The prospect of free money attracted more and more people –

men I should say. New projects were started, but still the army of men wanting

jobs rose. They started paying them less, but though the mood grew angry, the

workers continued to turn up. Meanwhile, the Provinces were indignant that Paris was receiving

immense subsidies. In June, The National Workshops were disbanded. The young

workers were given the choice – join the regular army or resign. The older ones

were offered work in the Provinces (to even the poorest Parisian, this was

tantamount to exile) or to resign.

The socialists also passed an excellent and enlightened law

restricting the working day to 10 hours. They calculated that not only would

this be good for those already in work but would create new employment. In the

21st century, the French reduced the official working week to 35

hours with something of the same aim. In both case something of the same resulted.

The nominal working week may have been reduced but employers resorted to

various shifts to ensure that they didn’t have to employ new people.

At the end of June, there was a mass demonstration. The

government put it down with troops and there were quite a few deaths. For the

Péchot family, the most vivid memory was the Archbishop of Paris, killed as he

tried to separate the troops of the Republic from the protesters. Most of the

nation, even the Decauvilles, considered the socialist experiment a mistake which had left most of the

population poorer. Between summer 1849 and 1851, the new laws were

rescinded or reframed and the new Republic lost its credibility.

|

| Louis Napoléon Bonapart, Napoléon III 1852-70 Courtesy MD Wright |

Cometh the hour, cometh the man. Louis Napoléon, nephew

of the famous Bonaparte, was by training

an artillery officer but had been trying to get involved with French politics

since 1830, attempted coups included. Although an unspent conviction hung over

him, he headed up a Bonapartist party and gathered up support over all the

‘anti-socials’ over the months that followed. Thanks to his manoeuvrings, there was a

plebiscite in December 1851 to make him president for life. This election did

not take place under completely free and fair conditions. The Second

Empire under Napoléon III officially began in 1852. By

luck and adroit concessions, it lasted until 1870. The Empire enjoyed years of

prosperity, helped by expansion of the railways bringing trade and

connectivity.

The railways, by design, were to radiate from Paris in an orderly

fashion. In 1852, there were short networks around Lyon, Marseille, Paris itself and to some

extent in the north. As boys, Péchot and Decauville rejoiced as city after

city were connected to Paris. In 1854 it was Balfort in eastern France. In the same year, it was Lyon, in

1856 Marseille. Connecting western France was more difficult as the

probable traffic was less. Rouen, further down the Seine, mid 1840s, was fairly simple but a line from Orléans to Bordeaux

was in doubt. The free market were never going to go to the expense.The government had to permit the Paris-Orléans to build a second route to Lyon, rivalling the one already built by the Paris-Lyon-Marseille. They threw in a few other goodies which had nothing to do

with western France.

Despicable! Unfortunately for the Péchots, the line to Brittany was considered ‘uncommercial’ and

the Ouest Company which was supposed to build it was not very profitable. Various inducementswere made. Paris even had to finance an Etat/State line to cover the least attractive routes.

|

| Quaint 2-2-2 of the Ouest Company assured the Paris Rouen route in the late 1840s |

A number of ventures

abroad seemed to go the way of Emperor LNB, until he tangled with Prussia. The

ensuing Franco-Prussian War was by general admission a defining moment for all

the French, not least Decauville and Péchot. Eastern France was overrun by Prussia and her allies, the French regular army

either imprisoned or penned in neutral Switzerland,

LNB was ousted and France

declared a Republic. All was not lost. Paris was heavily

defended by a series of forts and moves to create a Citizen Army were

successful. Every able-bodied Parisian was enlisted in the garde nationale and

paid 1.5 francs a day. A corresponding garde mobile was to be formed in

unoccupied France.

Then and later, there were parallels with the national workshops which would

come back to bite the administration. The young Paul Decauville was a proud

member of the garde nationale, Prosper Péchot a brevet lieutenant commanding

the garde mobile in western France.

Unfortunately, the Germans had the experienced soldiers, the

railways and the industry of France.

Efforts to create new armies in western France were hampered by the lack of

resources, not least railways.

Decauville was to vividly remember the problems of carrying

ammunition to the guns defending Paris.

Péchot was to remember his experience transhipping arms from railway wagons to

horse-drawn carts and then back again, depending on the position of the enemy. Both

were determined to find better transport for the future.

On January 17th 1871, in a ceremony held in he

Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, the Germans

created a new Emperor - Kaiser Wilhelm 1, aka King of

Prussia. In February, the French sought an armistice which was

ratified by a new Parliament in March. Peace terms were a humiliation, a huge

transfer of money to Germany,

the loss of territory and 1.6million inhabitants. The Germans kindly allowed

those who wanted to leave to do so – with what they could carry – so there was

a refugee problem as well.

|

| The battle of St Privat 1870. One of the humiliations of the French defea was that their troops had to fight civilians in 1871. Illustration courtesy Raymond Péchot |

To make matters worse, the new Parliament cancelled the

wages of the garde nationale. Paris had been one

of the few regions to have voted against the Peace with Germany, now

the inhabitants were being pauperised. There followed the Paris Commune. From 3rd

April onwards, there was violence. The Germans, having no doubt a sense of

humour, allowed the release of no less than 150,000 French troops. These were

forced into battle against the Commune who resisted fiercely. Estimates of the

dead vary between six and seventeen thousand

From this unpromising beginning was born the Third Republic

and the Belle Epoque. In the period, between the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris

Exhibition of 1889, Paul Decauville turned a small family enterprise into a

portable railway system which became famous, and imitated, around the world. Prosper Péchot invented a military version

which was capable of moving millions of tonnes of freight. Neither man would

have been so driven if it had not been for the experience of youth.

To be continued...

|

| To be continued - the creation of the Péchot wagon |