In the Works

Saturday, 18 January 2025

The 14 to 18 war and how human nature wins

A happy new year to you all! It has been a busy twelve months for us but the Workshop has been peaceful - for a number of reasons. We are hoping that this time next year, Malcolm will be in there doing what he loves - creation. Alas, some of his suppliers have ceased trading and so the options for making a new batch of locomotives are limited, but there are still three possibles, the Wren (pictured - credit MD Wright) the Quarry Hunslet and the Baldwin Gas Mechanical.

And now to the title of this blog. This suggests that whatever is said or written, human nature goes its own sometimes contrary way even in wartime and under military discipline. The Mission Satement for both sides was 'Win at all costs!' but what happened on the Western front was more nuanced.

From late 1914 to early summer 1918, the position for most of the combatants was effectively stalemate. Millions of troops from the Allied and Central Powers (mainly Germans) faced each other over a Front of around 500 miles/800 km. As the gentle reader knows from previous blogs, supplying them was only possible because of a network of 60cm/2’ gauge railways. The British were late into that game but within a couple of years were as railway-minded as anyone.

Since 1888, their Allies, the French had a 60cm gauge railway that could cope with conditions in the field yet transport the thousands of tonnes of supplies required by a vast army. The illustration, courtesy of the family of Raymond Péchot, shows how a 36 tonne gun barrel could be transported on light prefabricated track. The secret is that the weight is supported by no less than 12 axles, reducing the force on the rail to a tolerable 3 tonnes. An inspired and industrious Artillery officer, Prosper Péchot, first designed the system and then master-minded its official adoption, a lengthy process. The British were initially suspicious of such railways. Eventually they realised the potential of the system although it required a cognitive revolution by the ‘Top Brass’ and the civilian administration, another fascinating story.

There was a related ‘bottom-up’ revolution. Over the weary months, troops on both sides got to know each other, and the better they did, the more likely they were to co-operate in staying alive. This was a secret between them, known to junior officers but fortunately not to the generals or journalists who were led to see what they expected to see, eg trench raiding parties, roads covered with a torturous procession of small lorries toiling along the Voie Sacrée to Verdun etc. The real action was taking place elsewhere. The motor vehicles transporting token loads to Verdun and the gallant troops singing the Marseillaise were, almost if not completely, window-dressing. Under trench conditions, more effort was put into evading death.

Ian Hay, the Britsh novelist, joined up in September 1914. He was promoted to that most difficult of roles, junior officer, by February 1916. At that point he wrote the following:

‘the winter of our discontent is past.(At least we hope so.) Comfortless months of training are over and we have grown from a fortuitous concourse of atoms to a cohesive group of fighting men. … active service is within measurable distance and the future beckons to us to step down into the area’ (the First Hundred Thousand Ch 12 p 114) His batch of warriors then waited for the First Half Million to be trained before they entered the field of battle. ‘Thereupon we shall break through the German line at an unexpected point and roll up the German Empire as if it were a carpet and sling it into some remote corner of Europe’ (op cit ch 13 p125) Up to that point, there was nothing in his sentiment to worry Top Brass or the Press. This beautiful illustration by Georges Michel, from the author's collection, shows a section of No-Man's-Land lit up tracer shells.

The Black and White Highlanders, the novelist’s fictitious name for the Argyll and Sutherlands, arrived at the Front of the Front on a bad night. Relieving parties were usually able to march up to the reserve trench and then proceed from there to the Front. That night all occasions conspired against them; they arrived late. The good news was that they missed most of the night’s many duties – transport of food, water and ammunition, evacuation of the wounded and burial of the dead. Their commissioned officers missed out on form-filling of reports and statistical returns to be passed on Battalion Headquarters. These in turn would be forwarded to ever-more heady Headquarters until they arrived at what Hay was pleased to call Olympus.

The bad news was that the German artillery was active on the night they arrived. The euphemism was ‘distributing coal’ – a lot of ‘coal’ most enthusiastically distributed. They couldn’t use the communicating trenches but had to make their way through a maze of temporary, half-dug and semi-submerged scrapes in the ground. In order to progress half a mile, they wriggled and crawled about four(6.4 km). Dragging themselves along was one thing. In addition to himself each man also carried the equivalent of a second person – his kit. Let others sing of the glories of the full kit ordained to be carried into action, for ‘here my Muse her wing maun cower, sich flights are far beyond her power’. Let us just say that many items were obligatory but the individual could also bring any ’extra’ apart from ‘unsoldierly trinkets.’

They reached their destination wet and exhausted. This illustration, also by Georges Michel, author's collection, shows exhausted comrades bedding down in what is little more than a scrape in the earth, running water plentifully supplied.

After 24 hours, they began to get a feeling for trench life. It was once more dark but ‘there is an abundance of illumination; and by a pretty thought, each side illuminates the other.’ The Germans supplied star-shells, magnesium lights and searchlights and the British did their best to return the compliment. ‘The curious thing is that there is no firing.’ An informal truce exists ‘founded on the principle of live and let live. As long as each side is busy digging trenches and drawing rations, they won’t stop the other from doing the same. Thus neither side have to fight on an empty stomach’. If you look at the two Michel pictures, you will see that no-one is actually firing at the enemy.

The agreement was not perfect. Some sentry, usually new to the Front, would imagine a phantom army approaching. 'His rifle fires, another replies and then both sides are at it. But after three minutes, as likely as not, the firing stops and shelf-stacking resumes.' (op cit ch 18 pp 186/7) Later in Chapter 18 of his book, Ian Hay describes the aubade which regularly accompanied the dawn. Was it mist or is it a gas attack? Probably just mist, but a god-send for the junior officer who had a report to fill in. Rather than leaving the paper blank, he could mention a suspected gas attack. On most mornings, there would, in fact, be a spontaneous ceasefire between dawn and nine while both sides broke their fast. Between nine and two, for German Top Brass were creatures of habit, their artillery would engage in sufficient shelling to impress the officers. They tended to aim for the trees. When the officers took their break for Mittagessen, there was a grateful pause when the rank and file could grab a much-needed forty winks.

An eager general, an officious junior or a few ‘sooks’ among the private soldiers could have surprised the enemy, cut off his supplies and vastly increased the kill-rate. Here is a close-up of a Minnenwerfer, literally Mine-thrower, always available to the Germans but not in constant use. This picture, from author's collection, shows the very high angle of fire, ideal for sending the missile straight up, over the short distance of No-Man's-Land and then down on enemy heads.

The next illustration shows a gloomy German detail dragging the Minnenwerfer. The infantry disliked the artillery and no doubt the attitude was reciprocated. A parallel situation held good on the British side. A machine-gunner would sneak into a trench, fire off a few (thousand) rounds and then decamp, leaving the defenders to suffer the returning fire. The same would happen when a trench mortar was sent in. The missiles were fewer but larger and resented even more. If a ‘mortarer’ was seen approaching a section of trench, the Major was hastily woken. Such an officer was of sufficient seniority to order the fellow to remove himself and his contraption. The trench mortar officer would drift on, looking for another site in which to perform his unpopular entertainment.

The Germans had their share of sooks and psychopaths and, as we have seen above, in the Minnenwerfer an even nastier toy. It was a tiresomely efficient short range missile launcher, ideal for getting a bomb over a trench parapet. It was possible to follow its leisurely parabola and inevitable fall somewhere near the observer. The spring controlling the percussion cap gave the bomb ten seconds to settle before initiating the explosion. As the bomb contained 15kg/over thirty pounds of high explosive, the damage within an open trench was considerable.

There was a reply. ‘Minnie’ usually fired at 14:00 precisely. Any trench suspected of harbouring her was blasted with everything the British Army and Royal Flying Corps had to hand. It was important to do so at 13:55, or thereabouts - as long as it was before 14:00. One suspects that as well as being a creature of habit and discipline, the ordinary German had a sense of humour. He used the predictable habits of the British soldier to get back at unpopular officers. The illustration, author's collection, shows a gloomy detail of German infantry dragging the Minnenwerfer. It was light and easily transportable.

This mixture of peer pressure, common sense, empathy and restraint seems counterintuitive. It appears to go against human nature which allegedly informs us to hit back, and hit back harder - with corollaries such as pre-emptive action. Instead, the people facing each other across no-man’s-land had an elaborate system of coded messages of peace, slow to anger, quick to respond to efforts to de-escalate rather than to escalate a quarrel. If only the combatants of today remembered these hard-won lessons of 14-18.

In the words of Philip Ball, these compacts between opposing sides ‘do not begin as a humanitarian agreement, quite the contrary. It is enforced by killing. Both sides realise that if they flout an unwritten agreement in order to gain an advantage, they would get as good as they gave.’ But the side which had been provoked was careful to restrict any damage. They would give the provoker a chance to back off to the status quo. (Critical Mass ch 17 page 520)

Certain groups would do well to pay attention. It has to be said that the game of Tit for Tat is best played between the same sort of people. On the Western Front, both sides were a mixed bag of European males with a lot in common. If they didn’t actually empathise with the opposition, they knew enough to make a fair guess at what they were thinking. They didn’t even have to share a language to make unspoken agreements stick. What they did share was pretty well the same patch of mud.

Robert Axelrod investigated the Titfer theory and demonstrated that a Tit For Tat strategy could work. Rather than dismissing an opponent as a consistent enemy, it encourages co-operation and discourages the pre-emptive strike. What’s good enough for vampire bats, sticklebacks and monkeys could well be good enough for us. We can hope.

This picture, courtesy MD Wright, shows a Wrightscale model War Department Baldwin 4-6-0T

Robert Axelrod Evolution of Cooperation Basic Books New York 1984 The theory needed a fair bit of refining – sixteen years of it.

Philip Ball: Critical Mass

Ian Hay aka Major-General John Hay Beith: The First Hundred Thousand Richard Drew Publishing Glasgow 1985

Sarah Wright: Tracks to the Trenches Birse Press 1914

And here is a presrved WD Baldwin 4-6-0T, photo courtesy MD Wright

Wednesday, 23 October 2024

60cm gauge and northern France

We have just visited the Baie de Somme. As everyone knows, the estuary of the Somme is on the coast of north-west France. It has been celebrated by soldiers, fishermen and artists. We were fortunate enough to have a room in St Valéry facing east and saw the sun rising. The view on to that little piece of sky were spectacular. You will be pleased to know that the sights of St Valéry are celebrated in the Journées de Patrimoine held annually. More of that later.

The area is certainly picturesque and by t eninteenth century, it attracted tourists. It has always been unique.Coastal erosion from Normandy was washed up on the Somme coast, for what the sea takes away, it gives back somewhere else. It created the Marquenterre, a picturesque but treacherous border between land and sea. Towns such as Rue 10km/6miles north of the bay used to be on the coast and the river Somme is only navigable because it is canalised through the encroaching silt. From the 1755 onwards, there were determined official efforts to clear channels through fresh and tidal waters. Legends accrued, typical of a liminal areas, of sea monsters and shells which could grant wishes. Stories that were good for frightening naughty boys and excise-men were repurposed for entertaining the visitors.

To cater to the tourists, a metre gauge railway was created, the first branch of which was opened on 1st July 1887. The picture above shows an 0-6-0 T steaming into St Valéry. The railway ran from Noyelles station on the standard gauge line to Le Crotoy to the north side of the bay. The opening was to coincide with the summer holiday season; Le Crotoy is a delightful seaside town. By 1900, the metre gauge system extended right round the bay; from its origins in fishing and mineral extraction, Cayeux also became a holiday resort. Sea bathers could spend the whole summer here or pop down from Amiens for the weekend.The sketch below shows the Bay. I have missed out a couple of names. Sorry! You will infer that St Valéry is the large town at the east end of the Bay. Cayeux is due west, just below Le Hourdel. The small 60 cm line continues up the coast to Brighton, yes! Brighton Beach!

The area produced ‘silex’ ie silica in a pure form.

A bountiful current brought to Cayeux not silt but galets/pebbles. Indeed the name Cayeux means caillou – pebble.

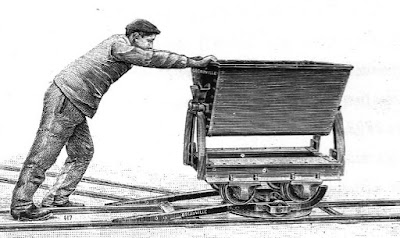

Before the coming of the railway, these galets were gathered on the coast-line by ramasseurs, often women, who filled up baskets about 60cm/2’ in diameter. They were then loaded into rafts for transport onwards. The galets were crushed and used as building sand, aggregate, as abrasives and a component of the local faïence/pottery. Raft journeys were laborious and hazardous and so by the 1880s, temporary Decauville tracks were laid to aid in the harvest. Tipper wagons took these to the port, canal or station. The picture below shows ramasseurs and, in the background, a 60cm line. Below is shown a maker’s illustration of the standard tipper wagon. Tremendous muscle power must have been needed to lift a laden basket but at least it wasn’t necessary to stagger all the way to town.

This picture is courtesy of BK postcards, Paris

A 60cm gauge railway was planned to link the cape of Le Hourdel to St Valéry but the coming of the metre gauge system supplanted it. For more information, you can consult the County Archives in Amiens; document reference M. de Raesfeld. Quend Plage and Fort Mahon Plage, about fifteen miles north did build 60 cm holiday railways for themselves. Under sadder circumstances, 60 cm came back to the coast; more later. A metre gauge network, totalling at its zenith almost 150 miles, connected the towns round the bay – also the valley of the Authie about 20 km north and a separate network in the Upper Somme. Ironically, the network included a standard gauge branchline – between Ault on the coast and Woincourt! Here is a general map, showing the metre gauge line going off east towards Dompierre in the Authie Valley and standard gauge north to Boulogne and Calais. Again, apologies for failing to name St Valéry.

St Valéry, at the centre of the bay and the best known of the towns, has been a port since well before 1066. It took its name from a 7th century holy man, so say Philip Pacey and the Service Culturel of Le Crotoy. The fleet of William the Conqueror stopped there, waiting for a wind to take them to England. Edward III of England came to the area on a revenge expedition; Crécy lies between the Somme and Authie valleys. We took the kids once but although they know all about 1066, slavery and trench warfare, this particular Battle of the Somme had completely passed them by. The sea coast was also a Front in Napoleonic times. Spies from England slipped to and fro using fishing boats operating mainly from Boulogne but when things got too hot, they took refuge in quieter spots such as St Valéry and le Tréport. By keeping on the move, they were remarkably successful in evading the spy catchers. As Flaubert remarked in his Dictionary of Received Ideas, Chemins de fer: Si Napoléon les avait eus … il aurait été invincible. If Napoleon had had railways, he would have been invincible. But he didn’t have them.

In the First World War, all the small Channel ports were used to import supplies and people and export the ‘empties’ ie used shells, troops on leave and the many casualties. St Valéry alone landed 109,000 tons of freight in 1917. The most remarkable railway achievement was the Ligne des Cents Jours – the railway built in one hundred days. As all those who follow my blogs know, the Germans launched a Michael/Spring Offensive on 21st March 1918. In a few days, Amiens was threatened. It was the site of a vital railway junction. To provide new links between the Channel ports and the Front, a new standard gauge line was built from Noyelles to Feuquieres (on the line to Rouen). It offered a north-south rocade/bypass for all the small lines going inland from the Channel ports. From Noyelles going south remains can still be traced. This small map shows the Ligne des Cent Jours and how it intersected with two of the junction, the one with Noyelles itself and with the line to Le Tréport.

Postwar, an order for 11 brand-new 0-6-2 locomotives were ordered from Haine St Pierre in Belgium and some second hand railcars were later acquired – not much for such a lengthy network. By the 1930s the whole network was tired. Acquisitions were mainly second-hand from closing down sales occurring at other networks.

During World War II, the area was once more a Front – between Occupied France and Britain. This picture shows a tipper wagon running on light prefabricated rail. It is clear that it is hard work. From 1940, the RAF conducted bombing raids. In 1942, when Hitler turned his attention to Russia, the Organisation Todt started building the Atlantic Wall to keep out Britain and the Allies. Remains – a blockhaus, tank traps and launching ramps - can be seen at Fort-Mahon-Plage. We saw the foundations of a blockhaus – the Nazi equivalent of a pill box. Signs of the 60cm line running from Le Hourdel to Cayeux can be seen from the air. Quarries for high quality building sand and aggregate. were updated and augmented with Atlantic defences. Levies from the local people provided labour. Although their sympathies were unlikely to be with the gang-masters, soldiers and civilians alike suffered from Aliied aircraft. This map shows significant 60cm railways. The lomgest one, running from Lancheres on the metre gauge to Ault was a Nazi construction.

The Germans withdrew on 2nd September. The beaches had been turned into mine-fields, the resorts which were not fully destroyed were damaged and the metre gauge seemed on its last legs.

After the War metre gauge throughout the département of Somme rapidly declined. The inland branches closed first. Noyelles to Le Crotoy closed in 1969, Noyelles to Cayeux in 1972. Help was at hand.A vigorous preservation society was formed. The Chemins de fer de la Baie de Somme (CFBS)was founded in 1970, officially 1971) and has now been going for 50 years. It has a regular time-table in summer and we were fortunate enough to see it on a journée, well, weekend de patrimoine 20-22 September. We enjoyed the railway architecture, a de Dion railcar and a Pinguely 0-6-0 steam locomotive.

For more information about Baie de Somme www.baiedesomme3vallees.fr

Ch’tchot Train was the newsletter of the Chemin de fer de Baie de Somme

This Dark Business Tim Clayton Abacus London 2018

Railways of the First World War WJK Davies David and Charles Newton Abbot 1967

Railways of the Baie de Somme Pacey, Arzul and Lenne Oakwood Press Monmouth 2000

Tuesday, 16 July 2024

Franco Prussina and Great War

Pechot and Kitchener

Prosper Péchot (1849 to 1928) was very different to Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850 to 1916). For a start, one was French, one British, one a mere Colonel, the other a Field Marshal, one a Sapper, the other in the French Artillerie, but the two both influenced the course of the First World War.

Their early lives crossed. In 1870, Kitchener was in western France, staying with French relatives when France declared war on Prussia on 18th July. Prosper Péchot was finishing the first year of a course at the celebrated Ecole Polytechnique in Paris as Army officer-in-training. This sketch, author’s collection, shows a contemporary French fantassin. He carries the chassepot rifle, his kepi is blue and red, his coat blue, trousers red and the outfit is completed with white spats.

On 19th September, when Paris was besieged by the enemy, Péchot was on sick-leave. His fellow students enlisted as a man to defend the capital, but he was convalescing back at home in Brittany. The advancing Prussians had captured or contained in one way or another most of the regular French army; the Second Empire of Napoleon III was replaced by a French Republic. Some might have sued for peace, but Paris and western France did not give in. This sketch, author’s collection, shows a member of the Prussian infantry. He is wearing the distinctive cap in dark blue with its small white emblem, dark blue tunic and black trousers tucked into the famous German Army boots. The equally famous greatcoat is slung across one shoulder. His right hand holds a Dreyse rifle with fixed bayonet.

The Prussian Army numbered around half a million. It is true that half this number were employed in starving out Paris, guarding prisoners of war etc but that left quite a number to mop up the resistance. There were about 95000 French regulars at liberty. Amazingly, over the next four months, they were boosted by half a million volunteers.

Both our heroes were stirred by this activity. Kitchener joined a Field Ambulance Brigade but found time to take a trip in a balloon to see the ‘Army of the Loire’ in action against the Prussian foe. It was cold, of course, as it was winter and colder still up in the balloon. He caught pneumonia and was whisked back to England. He was commissioned into the Royal Engineers on 4th January 1871.

Once Péchot had recovered, he too reported for duty and was assigned a transport detail in the Rennes area. The trouble was that the Armi(es) of the Loire formed and reformed. Numerous but inexperienced and totally untrained, they were no match for the German regular army. When defeated, they melted away and blended in with their French fellows. It meant that Péchot and his team never knew where to dispatch supplies. In the end, as he recalled, they were just trying to keep supplies and themselves out of the hands of the enemy. On 28th January 1871, the young Republic capitulated. Among all military goods, Péchot’s arms and ammunition were now ceded to Germany.

Their services to France had its effects on future careers. Kitchener was reprimanded for embarrassing the British Army. He had violated its strict rule of neutrality towards the War. He was shipped off to the colonies, dabbled in imperial adventures and learned fluent Arabic. In the end, it did his career no harm.

Young Péchot was haunted for life by the French defeat. He was also frustrated by how little he could achieve as a serving officer, given the state of French railways at the time. He vowed to improve matters. He realised that without efficient logistics (my modern term) an army could not fight a modern war. He invented, with help from Paul Decauville – also seared by his experience in 1870-1) – the Péchot system of portable 60cm gauge railways. The fruit of Péchot’s labours was the sprung bogie and bogie wagon. This drawing appears courtesy of Dr Christian Cénac. The wagon could run reliably on hastily laid prefabricated narrow gauge track yet it could carry ten tonnes of supplies - across fields or unpaved roads. It was the best transport available before tracked vehicles were introduced. He worked tirelessly to promote it.

In the time leading up to World War 1, Kitchener’s career blossomed. When he was young, he was a rapid adopter of technology, weapons and railways. He used his surveying skills and the newly introduced machine gun to terrifying effect at the Battle of Omdurman. He was heard to remark ‘We have given them a damn good dusting!’

It was a pity about all the deaths, but the Mahdist regime was not entirely pretty. Kitchener was able to free thousands of enslaved people. Kitchener made General before 1900.

Péchot’s career stagnated. In the view of his superiors, he was an obstinate Breton, obsessed with an expensive military toy. In a particularly mean move, they only made him Colonel in 1902, where he stayed until definitive retirement in 1911. His postings were always well away from Paris or Toul, the two places from which he did so much for his System. He had to make train journeys with, say, a 60cm gauge turn-table in his passenger luggage or personally push a bogie a couple of kilometres down the track. While these could be considered amusing anecdotes, it shows how far he allowed his superiors to push him in order to advance his cause.

Kitchener was implicated in the scandalous concentration camps of the Boer War but achieved a relationship with Louis Botha and other Boer leaders. This was to stand Britain in good stead during World War 1. He was created Viscount Kitchener in 1902.

THis photo, author's collection, shows Horatio Herbert, Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, in Field Marshal's uniform. René Puaux, writing in 1916, described him as a shining warrior who was a misogynist and lived only for the exercise of authority and his collection of porcelain. I wonder what Puaux really meant.

Péchot had a few career boosts. From 1882, when he had a fully designed and costed scheme, to 1888, he struggled to have his System recognised. In 1885, the French Navy, of all institutions, backed him to produce a ‘strike force’ which would enable marines to land on a beach, install a short railway and efficiently unload guns and material. In the 1890s, the Colonial Service made use of his ideas.

In 1888, serious trials took place, to see if portable railways could solve the problems of the Army. For once, Péchot’s ideas were given a fair trial. The background was this: France put a lot of faith in a curtain of modern fortresses which were to halt the enemy at the frontier. The advent of high explosive threatened these. A screen of earth sheltered defences were introduced to prevent the enemy from getting within range. The photograph taken by MD Wright shows the entrance to Fort Girancourt, one of the 16 forts built to defend Fortress Epinal. These fort were in turn screened by 34 redoutes and 60 gun batteries.

An adaptable railway system would be most useful in helping to build and supply such subsidiary fortifications. The Génie (Engineers) favoured metre gauge railways, the Navy and Artillierie 60cm. And in the end, who actually supported Péchot’s system?

Charles de Freycinet (1828-1923) was also involved with the Armies of the Loire. Léon Gambetta is the person remembered for escaping from Paris and raising new volunteers from the west of France. De Freycinet, though an engineer rather than professional soldier, was his enabler. It is not clear if he met Prosper Péchot, but he saw the problems that the young man was trying to solve.

De Freycinet had as successful a political career as anyone during the Third Republic; in 1888, he was one of the few civilians to hold office as Minister of War (equivalent to the British Ministry of Defence). Although he was not involved in professional in-fighting, his military service in 1870-1 counted in his favour. He headed up the Committee assessing the trials comparing metre gauge with 60 cm. If he backed either scheme, he would offend someone. He came down in favour of the 60cm System but tactfully gave it the official name of Artillerie 1888.

Ironically, the Germans adopted this system more enthusiastically than did the French. It is a proven fact that Germans were observing the French trials and within a few months, they abandoned their existing military designs and adopted, pretty broadly the French one. 60cm gauge locomotive-hauled bogie-wagons made trench supply possible for both sides during the First World War – guns, ammunition, engineering supplies, food, drink and the evacuation of soldiers and spent shell cases. Prosper Péchot was asked to come back to serve his country and provided technical leadership as France scrambled to update its military logistics. This picture, courtesy of the Péchot family, shows Propser Péchot in 1909, having received his Légion d'Honneur.

(Horatio) Herbert Kitchener is famous for providing the iconic recruiting poster from August 1914 onwards. He provided a powerful figurehead for attracting half a million volunteers to the armed forces but his ideas about technology had become somewhat outdated. He was infamous for discouraging the British from using field railways. Very soon after his death, War Department Light Railways came into being – but that is another story.

You might like to look at:

Dr Christian Cénac Soixante Centimetre pour ravitailler l'Armée francaise pendant la guerre de 14-18 (French language) This is a treasure trove of drawings of French 60cm gauge rail and rolling stock

René Puaux wrote in l'Illustration magazine, number dated 10th June 1916

Sarah Wright Colonel Péchot: Tracks To The Trenches This is the story of Prosper Péchot and his wonderful narrow-gauge railway system

Friday, 14 June 2024

Colonel Pechot and the Billy Goats Gruff

Firstly, an apology; in my previous blog, I referred to Hunger: How Food Shaped The Course Of The First World War. It is by Rick Blom and I read te translation by Suzanne Jansen. It is worth a read if you are interested in food.

My sub-title should be ‘Clément Ader and narrow gauge railways’but I will explain why goats come into the story. In Colonel Péchot: Tracks to the Trenches, I devoted a whole chapter and more to what Péchot’s son, Henri Péchot, called the Battle of the Gauges (bataille des largeurs de voie). Henri Péchot wasn’t referring to the battle between the Great Western Railway and other British Railway companies, fascinating though that story might be, but to a battle between The Génie and the Artillerie.

This photo, courtesy of the family of Raymond Péchot, shows 15 tonnes of gun being moved on portable railway track. The trial took place in 1886 to test the Péchot system.

The cause of the cintroversy was choosing a standard for French military field transport and the 'battle' took place in the period 1882 to 1888. The Génie, the equivalent of our Sappers, recommended waiting until a war began and then requisitioning civilian metre gauge railways, and repositioning them as needed. The Artillerie, in which Prosper Péchot was an officer, slightly less vociferously championed his portable system.

This drawing, courtesy of Jim Hawkesworth, shows a length of Péchot system portable track.

Péchot had devised a new tailor-made system of field transport in 60cm gauge. The politicians preferred the requisitioning plan which required no immediate cost. The Péchot system involved upfront expenditure and so the plan was all but stifled. If you want to know whether the Artillerie or the Génie won the battle, buy the book!

Revenons a nos moutons or rather nos chevres; you want to know where goats fit into the story. Prosper Péchot wasn’t the only patriot looking for a way to defend France. From 1871 until 1914, the nation smarted under its defeat, nay total humiliation, in the Franco-Prussian War. Every man, woman and child was keen to win next time … A number of schemes were put before the French Government to give their armed forces the edge in some future conflict. Péchot’s was one. Another was from Clément Ader.

Clément Ader (1841 - 1926) was a celebrated inventor, known as the Father of Flight, Godfather of the Bicycle and inventor of the telephone. But I have not taken up my quill to defend his claims against the Wright brothers, Alexander Graham Bell and the like. Ader put forward an audacious plan for a railway which could propel itself across open ground. He put it forward as a means to ‘transport the Army cross-country.’ In short, Ader had also grasped the problem that had bedevilled both armies during the Franco-Prussian War, that of mobility in the battlefield.

Ader’s first rail-related invention had been a chariot releveur des rails. Alright, I’ll get to the goats eventually.

This picture, author’s collection, shows his design for a 'detachable' railway for lifting and re-laying specially designed track.

In 1866, he patented this machine for re-ballasting the permanent way. The plan was to automate a hard and potentially dangerous job. A device unclipped, then lifted the rail and then passed it to the other end of the train where it was relaid and the sleepers refastened. While th erail was off the ground, the track could be re-ballasted. Ader took his idea from a similar system used in coal-mines. It worked!

These and other inventions caught the popular imagination. His electronic transmission of music from the Paris Opera, first unveiled in 1881, attracted four hundred subscribers. His aeroplane, Eole – God of the Winds – took off in 1890 and skimmed the ground for 50 metres.

We are coming to the goats and the chemin de fer a rail sans fin, the endless-belt railway. This picture, author’s collection shows the goats.

Always aware of the importance of publicity, Ader invited the Press to come to Buttes Chaumont, a park in the 19th arrondissement of Paris, on 12th July 1877. There he showed off his newly invented all-terrain tramway. I surrender ma plume to a contemporary journalist:

“Three small carriages were pulled by two goats. (The carriages) rolled on a curious endless railway whose parts were articulated so that, after the last carriage had passed, they could be lifted and pulled to the front of the train where they were laid down in front of the front wheels of the leading carriage. What really impressed the spectators was that two goats provided quite enough pulling-power; without any sign of strain, they pulled not only three carriages but also twenty passengers.”

The demo rig was taken into the Jardin de Tuileries park in central Paris where it operated for the rest of the summer, carrying successive parties of children while proud mamans et gouvernantes looked on. Then the rig was dismantled.

The picture, author's collection, shows, in sketch form, the endless belt device. The track runs along under the carriages and then is taken up and runs from the back towards the front wheels, goes round them and is pulled back to the ground.

Charming though this picture was, Ader had a serious aim. He had hoped that this model would be scaled up. Instead of an upmarket goat-cart, a steam engine would pull military grade freight. Equipped with these new caterpillar-tracked trains, the French army could be supplied along country lanes or even across meadows. But it was not to be. The Services Techniques of the French Army who were later to give Péchot such a hard time turned down this delicious invention.

Writing for Illustration magazine in 1941, Jacques Faure commented that in the end, Ader’s invention of the auto-chenille – robot caterpillar – resulted in the ‘king of the battle-field’ – the tank, ultimate tracked vehicle. I’m not sure about that. Various men have claimed to have fathered the tank. Patents, whether registered or not, had appeared since 1837. The best attested appearance of an actual tracked vehicle had been one made by the Fowler Company which appeared at a steam-ploughing competition in 1861, well before Ader’s and indeed the Franco-Prussian War. Moreover, the tank in itself wasn’t king of the battlefield. The Allies introduced the tank during the battle of the Somme, two years before the end of the war. By 1918, the Germans had time to field a few tanks of their own. Péchot’s invention on the other hand, also adopted on both sides, directly enabled trench supply from 1914 to 18.

This illustration by Francois Flameng, author’s collection, shows a tank of 1918. The enemy it is about to crush look suitably terrified.

But this much is true. Ader’s idea was one of the great might-have-beens.

Mechanical descendants of the goats in the Tuileries Garden could have hauled guns to bridges over the Rhine:

Goat: Trip trap, trip trap.

The troll living under the bridge): Who’s that going over MY bridge? I’ll eat you up!

To which the reply: It’s ME, Big Billy Goat Gruff and I’m going to knock you into the water!

I’m not joking. When the 14-18 war began, the French marched towards the Rhine to retake their ‘lost provinces'. Their attempt to cross met with stern resistance. Meantime, the Germans were crossing into northern France by way of Belgium.

You may like the following

Rick Blom Hunger Unicorn Publishing London 2019 Translation from a Dutch original

Jacques Pradayrol Voie Etroite French language magazine of the Association Picard pour la Preservation et Entretien des Vehicules Anciennes is always interesting, especially numbers 75, 76 and 77 (April May 1983, June July 1983 and August September 1983) In Number 77 page 11, Jacques Pradayrol quotes Henri Péchot.

Illustration Magazine 13/03/41 page 268 article by Jacques Faure

La Liberté French newspaper established 1865, last edition appeared 1940

Sarah Wright, Colonel Pechot: Tracks to The Trenches Birse Press 2014

Thursday, 4 April 2024

60 centimetres and the battle of the stomachs

We are sorry that we won't be able to attend the 16mm Modellers' AGM at Stoneleigh on April 27th. We wish all our friends a good day and happy steaming!

When war was declared in 1914, both sides had their reasons for assuming it would soon be over. The Germans believed that they could score a mighty victory in the west before having to turn east to defeat the Russians. The British and French believed that the Germans would soon run out of nitrates to create ammunition. Both sides were to be disappointed in their hope of a quick victory. The nearer the Germans were to Paris, the more exiguous the supply lines. Nearly half a million got to within 40 kilometres of Paris but by then they were exhausted. They were threatened by flank attacks to both sides. If they couldn’t find food, they often found alcohol. Thirsty as well as hungry it was hard to make plans and easy to drink to excess.

The picture above shows an artist's impression of trench warfare on a good day; trench life was going to be the general experience of the Western Front. Both sides discovered that their enemies were resourceful, resilient and determined. The Germans were pushing forward until early September. Then they went into reverse. ‘Under our eyes’ reported a British Major in the valley of the Marne, ‘the enemy wheeled round and retired.’

The Germans fell back to a better line of supply and started to dig in. The pursuit was checked and the British and French dug in. From this ad hoc beginning came two lines of trenches, facing one another. The Allies waited in vain for enemy guns to fall silent; the Germans had a new supply of nitrate and therefore explosives.

The infantry were even more disappointed than the Top Brass. Trench warfare turned out to be heavy work with the all present risk of injury, carried out twenty hours a day in the cold. In order to fuel this effort, the poilu – French soldier – was allotted a theoretical 4,500 kilocalories per day (roughly four times that in kilojoules). It is not clear if the ration of ¼ litre of wine, also rich in calories, was on top. Over the course of the War, the amount of this cheer increased, in some parts to ¾ litre. The British Tommy received an equally theoretical 4200 kcal daily. They also received a largely Platonic rum ration. It came in a stoneware jar labelled SRD - service rations department. Wags invented new names – Seldom Reaches Destination or Soon Runs Dry.

The picture above shows food carriers at work - in a prison camp but wil give an idea of the difficulty involved in transport of meals. The drawing is by J. Simont from notes made by a medic. The two French soldiers portrayed carried their soup kettle by hand side by side. The Russians slung their kettle from a pole and carried it in pairs, single file.

We must not neglect the Germans. Their ration, just under 4000 kcal, was scientifically calculated to enable the soldier to carry out his duties. If you want to know what it looked like, this was 200g of bread, 500g of biscuit, 375g fresh meat, 1.5 kilos of potatoes (or smaller amounts in fresh veg), 18g sugar and, definitely not part of the modern Recommended Daily Allowance, around 20g of tobacco. The Tommy had something similar; only more meat with cheese and bacon and ¼ pound of jam as well.

Few received their full ration regularly. Most food had to be prepared behind the lines. It was then carried along communication trenches to the Front. A full load of bottles were quickly smashed. Loaves seldom reached the Front intact. Biscuit or chocolate could be fairly simply could be carried in backpacks, but tins and the soldiers’ post were jammed on top. Worst of all were the containers of soup, stew or coffee; try carrying them along zigzagging trenches! These metal containers were positively dangerous. As they reflected the light, they created a prime target for snipers who knew the route of the communication trenches. We can see from the advertisement above promoting Vinay Milk Chocolate that the manufacturers knew just how popular a choccy bar would prove if other rations didn't arrive.

Gradually, distribution became organised. The Germans were first. They had come into the War with 1000 kilometres of 60cm gauge railways. These could be rapidly laid with little ground preparation and were invaluable for reducing the distance that human porters had to carry supplies. They also had Field Kitchens, affectionately known as Gulaschkanonen – goulash cannons – the official name was Heeresfeldkuche / army field kitchens. The appliances were well-insulated and used glycerine in the double-boiler to stop food from burning. The larger of them, Modell 1911, had a 200 litre cauldron and a water boiler for preparing hot drinks. The smaller, Modell 1912, just had the cauldron. A 1913 version included a roasting oven. How could you improve on perfection? (The British never quite succeeded in perfecting their field kitchens; they kept desperately producing new variants.)

The French were slower off the mark than the Germans in providing field transport and kitchens. Although they had the invaluable Péchot system of prefabricated rail, there was only about 600 km of it, already being used for defensive purposes. The picture above, courtesy of the Péchot family shows two loaded bogie wagons, one carrying stores for humans, the other forage for horses. By 1915, they had ordered more rail and rolling stock. Special schools were set up to train the soldiers in their use. In the field, they had their Soyer stoves, first used during the Crimean War. You will be pleased to know that the conscripts were checked to see if any were chefs de cuisine and their talents were put to good use.

This picture, taken by Jim Hawkesworth in the 1950s at Amberley quarry,shows an elderly but well-laden War Department D-class bogie wagon. British War Department Light Railways did not come into existence until late 1916 and so the British were ‘making do’ for far longer. The safest way to get food to the Front was in tins. Thomas Atkins used his ingenuity to warm up his supplies, sometimes with a commandeered stove, sometimes with candles. A tin of Maconochie stew could be opened and then placed over a ring of empty tins with half a dozen candles fitted into the centre. With this improvised chafing dish, the food soon warmed up. More usually the contents of the tin, whether Maconochie, bully beef or jam was consumed cold off a bayonet blade.

Tinned food was easier to carry but unfortunately, less easy to inspect, a fact which the war profiteers soon realised. The stuff they put in the jam rather than fruit and sugar! exclaimed a British soldier. When the USA entered the War soldiers claimed they were being forced to eat Monkey Meat.

There was less tinned food for the Germans. As the War dragged on, quality and quantity decreased, not because food couldn’t be carried or cooked but because of the blockade. By 1917, daily rations were often reduced to 300g of bread and a litre of thin soup. They were constantly hungry.

I mentioned the post. Letters to and from the Front were enthusiastically sent and received. The drawing above, also by J. Simont, shows a soldier in a trench writing home by torchlight. On each side of him are sleeping comrades. To his right is the profile of the soldier doing sentry duty. In a previous blog, I mentioned gifts that the ingenious poilu would craft from spent ammunition. In return ‘home’ sent a variety of comforts. The French sent wine of course, preserved meats, chocolate and various patent foods, such as Phoscao chocolate flavoured breakfast food, Poulain Supraliment (superfood) and Vitry chocolate. The manufacturers advertised these enthusiastically in the Home press. French ladies in particular were encouraged to become marraines/godmothers to the heroes at the Front. You could of course put yourself down to be adopted by more than one benign lady but that meant a lot of extra correspondence. The British were urged to commission Fortnums Hampers; every family sent supplies according to their means.

These parcels travelled along with all other essential supplies. From the post offices, they were taken by Standard or Metre Gauge train to the major centres – Amiens, Epernay etc. Then they went to trans-shipment centres nearest the Front. They were loaded on to the 60cm trench supply network then taken to bases near the Front. Packed on top of the rations, they were carried by brave over-laden messengers up the zigzag communication trenches. Finally they arrived at the dugouts at the Front. What happened, you may ask to mis-directed mail or, sadly, to the mail for the many casualties? There was an unspoken rule that parcels (not letters) were opened and enjoyed by the soldier’s mates – one way of toasting the memory of a former comrade.

For more information, consult ‘Hunger – supply and shortages on the Western Front’ and ‘Colonel Péchot: Tracks To The Trenches’

Illustrations are author’s own except for the sketches of Péchot bogie wagons carrying supplies - courtesy of the Péchot family and the photograph of te D-class WD wagon courtesy of Jim Hawkesworth.

Friday, 1 March 2024

Von Tirpitz Coastal Battery

Of German Artillery

Though the German army never had a system of fortifications equivalent to the vast places fortes on the French frontier, see previous blogs, their defensive structures developed quickly up to and including the 1914-18 war. They had 60cm railways in readiness for offensive warfare which were quickly adapted for trench supply. Their trench systems were well designed. A whole blog post should be given over to the matter. This blog focusses on one particular system, a battery designed to harry Channel shipping and protect their trenches. The photograph shows its importance; it has attracted heavy naval shelling as can be seen from all the craters. It was supplied by a double-track 60 centimetre (the term used by 'Illustration') railway just visible running along in front of the four circular gun emplacements.

A description of this fortification at Ostend appeared in ‘Illustration’ Magazine in November 1918. The writing is partisan, but interesting. The journalist slithers between admiration for the brave poilus who retook the massive fort – implying great courage - and contempt for the Germans. They were at once stupid to his mind and also crafty and underhand. I’ll give you the flavour of his account and get in some mention of 60cm railways. 60cm is the English translation of voie de 60 which is the more normal French name for that railway gauge. Yet it was not used in this French language publication. The reasons for these linguistic gymnastics deserve a blog to themselves.

The ‘Illustration’ article centres round the von Tirpitz gun battery, the most westerly of a chain along the coast of occupied Belgium. It was particularly well-placed for its job and was named for Admiral von Tirpitz who is (dis) credited with devising total submarine warfare. This doctrine basically identified all ships, including civilian even if owned and operated by neutral countries, as combatants if they were even partially involved in Allied trade. This doctrine hurt the Allies who were supplied by sea more than were the Central Powers. Threats to respond in kind were no taken too seriously.

The map showing the coast from Ostend to Dunkirk places the von Tirpitz battery in the south-west suburbs of Ostend. Its armaments had a range of 25 kilometres. Thus it threatened both Channel shipping and the Yser front, where the trench systems of both belligerents met the North Sea. The local soil was sandy, both good and bad for construction; good because earth sheltering was relatively easy to arrange, not so good because deep foundations for walls and platforms were necessary. The complex took nearly a year to construct but after that, as long as repairs and improvements continued, it was nearly impregnable.

The long range was possible because of its 280mm naval guns, four in all. Of its many targets, Nieuport, on the French side of the Yser Front, was most affected but the port of La Panne was also vulnerable. The guns had a network of observers based at ‘telemeters’ - literally distance measurers. These tall masts were observation points for range-finding. The photo shows one lying across its concrete base; you can see the camouflage paint quite clearly. A common gibe levelled at the Germans of 14-18 was that they didn’t understand camouflage. If they didn’t at the beginning of the war, they were fast learners. In the centre background of the photo, another mast which is still upright can be seen. Two soldiers in the foreground give an idea of scale.

The four gun emplacements were circular concrete enclosures 15 metres in diameter and approximately 4 metres deep. See the aerial photo above. The concrete helped shelter the operators. The guns, manoeuvred by electric motors, were designed for different angles of fire. Those with a higher angle of fire, two out of every four, were in slightly deeper enclosures. The photo below shows the arrangement. A gun is pointing straight at the cameraman, the second is pointing up. To each side of these enclosures were earth sheltered ammunition stores, also protected by 2 metres of concrete. They were supplied by a double-tracked 60cm railway, an example of the Heeresfeldbahn, German military narrow gauge.

The Prussian Army had kept an eye on developments in Wales where the Festiniog Railway used 2’ gauge to great effect. In the 1870s, however, German narrow gauge concentrated on metre gauge with 750 mm a poor second. By 1882, they were looking carefully at the military narrow gauge devised by Paul Decauville and their establishments at Sperenberg conducted trials with 600 and 720mm gauge.

In the meantime, Prosper Péchot had devised his voie de 60 military system. By 1886, trials were taking place at the fortifications around Toul, in those days, near the German frontier. By the following year, Prussian Army research concentrated on horse-drawn 60cm gauge and the year after, when the Péchot-Bourdon locomotive was unveiled, suspiciously similar bogie wagons were drawn by suspiciously similar locomotives. After about 1890, the French lost their lead in the development of their military railways, but the Prussians and all the other German States kept revising and improving theirs.

The von Tirpitz battery benefitted from all this. The D-lok, pulling the Brigadewagen, was needed to shift all that cement for defence, and then the constant supply of 280mm shells for attack, not to mention constant repairs and improvements. The drawing, courtesy of Eric Fresné, shows the early Brigadewagen.

The entrance to the establishment was guarded by a further gun, and a barrack for the Other Ranks. The officers were housed in a smaller, more discreet shelter. On its substantial concrete roof were based two anti-aircraft machine guns. The whole complex was surrounded by barbed wire to discourage too much interest from civilians.

There was a substantial raid in 1916. Two guns were damaged, a claim verified by aerial photography. Repairs were rapidly effected and the battery remained active until the German retreat in late 1918. As a parting shot, the Germans laid booby-trap bombs before they left. The photo below shows sinister cables sneaking from the 280mm calibre gun running out into the sands where the detonators lurked. It also shows camouflage paint in use. Boooby-traps are not pleasant but neither is war. The more damage the Germans could do, the better the peace deal they could arrange, was their reasoning. If the Allies had had a chance to prepare such traps before the German Spring Offensive 1918, would they have behaved any differently?

It was a good example of fortification used successfully. Other forts had failed under enemy attack. Sometimes they were poorly sited or their defences were outdated, sometimes they had not been properly supported or maintained.

The illustratio9sn are from the author’s collection except for the drawing by Eric Fresné

See: Eric Fresné 70 années de Chemins de fer betteraviers LR Presse, Auray, France 2007

Sarah Wright Colonel Péchot: Tracks To The Trenches Birse Press 2014

Illustration Magazine Paris 9th November 1918

Eric Fresné is currently writing a book about 19th century French voie de 60 railways. We’ll supply further details in due course.

Friday, 2 February 2024

The illustration below shows a British gun mounted on a Péchot wagon - the 16mm model gun was made by Mr Milner, the wagon is Wrightscale and the photo was taken by James Hawkesworth. Thanks are due to all three modellers involved.

The French Army, led by the inspiring Colonel Péchot, devised a system of portable railways which should have given them an advantage when it came to trench supply during the First World War. The truth was more nuanced, though the French made all possible propaganda points that they could.

German guns were not brought to the Front by Péchot wagons. They were, however, quite good at shelling the opposition. The French tried to turn this fact into evidence of the brave fighting spirit of their Army.

‘The most desired gift from the Front’, declared Illustration magazine, ‘was jewellery crafted from spent ammunition, preferably German.’

Ladies were wild to possess a ring made by French soldiers in quiet hours from debris picked up from the battlefield. The fuse found in the front of a German 77mm shell was particularly prized, consisting as it did of a ring of just about the right size for a lady’s finger. The lower section, being larger and more chunky, could be turned into one for a man.

At first, the off-duty poilu (French soldier) simply used a penknife and then improvised files from the squad’s toolkits. Machine-gunners had a larger range of files to choose from; but everyone at the Front had a bayonet available. Because a bayonet blade is conic in section, the gentle steel curve, is ideal for sculpting aluminium.

Now that they were bitten by the bug, the poilus got more ambitious. They began to melt the metal to get better shapes. As they used helmets or spoons as crucibles, they must have been using other scrap metal; the melting point of aluminium is much higher than steel. Bellows to drive the smelting fire were improvised from bayonet bag, Army issues. Hollow tent pegs, Army issue being cylindrical, were used as moulds. The mould was cut open with the sharpened blade of a spade, Army issue. Scraps of ornamental copper, also scavenged from German ordinance, could be set into the ring with the awl found in the squaddie’s toolkit, Army issue. Further engraving could be done with an entrenching tool, Army issue, and a final polishing was effected with a lump of hardwood, suitably moistened.

You can imagine that jewellery making, with its joyful repurposing of Army property, was at first discouraged. But seeing how well it was received by the Home Front, and how it alleviated boredom, even giving the troops something to look forward to when they were bombarded, it became a symbol of military resilience and ingenuity. Even the naïveté of design became art to be celebrated.

The folks back home were treated to brave propaganda. The thing was, though, the German artillery had many more 'howitzer' type guns which could lob shells over the trenches on to the heads of their enemies. What is more, the guns did not need elaborate preparations for getting them into position on the battlefield. This one could be towed by four soldiers. Slightly larger ones needed a horse.

Illustrations are from the author's collection and from James Hawkesworth.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)